Sep 03

2012Art History, Contemporary Visual Art, Marie Antoinette, Sentimental Art

The Head of Barbie Antoinette

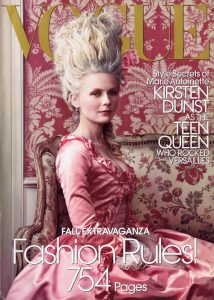

Cover of American Vogue, September 2006

The American artist Karen Kilimnik, who depicts bourgeois fantasies of aristocratic ‘decadence,’ has been hailed as ‘frothy, fun and the antithesis of everything great art should be’ (Neal, 2007: 100). Her portraits of movie-stars and celebrities posed as fairy tale characters and ancien-regime aristocrats include an image of the global heiress Paris Hilton in the guise of Marie Antoinette – ‘the teen queen who rocked versailles’ according to American Vogue (Vogue ed., 2006), though history knows her as a monstrous figure of decadence (a profligate spendthrift at a time of national bankruptcy) or a tragic scapegoat for the failures of the pre-revolution monarchy. Clichés both malevolent and tragic fade from Kilimnik’s and Sophia Coppola’s respective interpretations in which extravagance appears as a form of creative rebellion—‘the party that started the revolution’ as the poster-art for Coppola’s film exclaimed! The latter unfolds like an epic-scaled pop-video (the life of an 18th century ‘It Girl’); with not a severed head in sight and little allusion to the hardships of the peasant class. Whatever we might say about these historical blind-spots (Coppola’s Antoinette, though, appeared prior to the global economic crisis), there is no denying their negation of dramatic interest, suggesting that unchecked frivolity is as fatal to art’s powers of absorption as it is to its ethics. A similar candy-coated torpor infects Kilimnik’s practice which Donald Kuspit described as ‘hand-me down populism, a populism that has become so routine, even art-slumming populists find it boring’ (Kuspit, 2008: 8-9). Read more →