Oct 30

2018Alfred Hitchcock, Andy Warhol, David Lynch, Popular Visual Culture, Twin Peaks

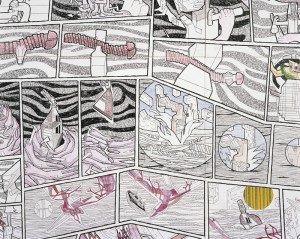

Twin Peaks / The Art Life

Twin Peaks, 1990, dir. David Lynch (still)

Possibly because my initial viewing of Twin Peaks: The Return (2017) coincided with my watching David Lynch: The Art Life (2016), I couldn’t help but be aware of the veiled allusions to creativity that occur throughout the wider series (including Seasons 1 & 2). It seems to me that much of the series’ imagery and symbolism relates closely to Lynch’s experience of making art, rather than necessarily to a bespoke mythology (though I don’t of course discount the theological significance of the “Lodge Lore” debated by countless fans). I also wonder whether the creative collaboration of David Lynch/Mark Frost derives from two contrasting views of the medium and form of television, one view emanating from painting (Lynch’s view), the other from literary fiction (Frost). In view of Lynch’s continued activity as a painter I am struck by the possibility that Twin Peaks may be referring to art history in addition to cinematic/ televisual references. (<<< SPOILERS AHEAD >>>). Read more →