The Wizard of Oz at the Glasgow Britannia Panoptican

The creator of The Wizard of Oz, Lyman Frank Baum, was born in 1856 in Chittenango in upstate New York, the son of a wealthy business man and investor who had made his fortune in Pennsylvania oil. Throughout his life he would have a number of careers, including as a newspaper journalist and as a playwright and actor working in theatres that Baum’s father owned; he also managed a fancy goods store known as ‘Baum’s Bazar’ in South Dakota, and worked as a travelling salesman for a china and glass company. In his spare time, Baum made up fantastic stories to entertain his children and these were so good that his wife Maud encouraged him to write them down. He succeeded in getting a number of his books for children published the most successful of which, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, made its first appearance in print in 1900.

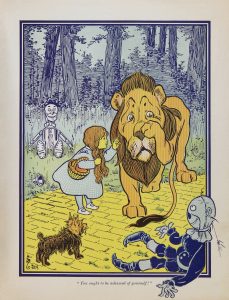

WW Denslow, Illustration to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, first edition, 1900

Baum went onto write a number ‘Oz books’ throughout his life all of which were very popular, and on the back of their success he financed and produced a musical version which premiered in Chicago in 1902 and later on Broadway. Despite the popularity of the books and the wealth and fame they brought to Baum, and indeed despite the fact that he had started out in relatively privileged circumstances, his life was dogged by repeated episodes of financial difficulty; this was a result of both bad luck and poor business-judgement. His last reckless ambition was to set up a motion-picture company in Hollywood (it is not often remembered that the first films set in Oz were written, produced and directed by Baum himself). But this venture also proved financially unsustainable and he was declared bankrupt for the last time shortly before his death in 1919.

It was not until 1939 that a film version would appear that would do Baum’s creation justice. It is thought that Metro Goldwyn Mayor, the most powerful studio in Hollywood at that time, was inspired to purchase the rights to Oz on the back of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) the first full-length animation produced in Hollywood and one of the most financially lucrative films released up to that time. The success of Snow White seemed to suggest that there was a market for fantasy in mainstream cinema that hadn’t been thought to exist previously and the MGM executives hoped to achieve a success that would rival Disney’s.

Backstage Trivia

The Wizard of Oz, 1939, dir. Victor Flemming (film still)

The Wizard of Oz was filmed in what was (at the time) a little-used three-strip Technicolor process, whereby the photographed image is exposed simultaneously onto three separate strips of black-and-white film each through a different coloured filter. Though this resulted in an excellent colour quality it was an extremely intricate process to handle and required enormous amounts of light to properly expose. Because of this, The Wizard was photographed entirely in-doors, on the sound stages of MGM; and what are called “matte shots” were used extensively to give depth to the simulated exterior landscapes. The latter device, through which a section of the photographed image is replaced with an oil-painting on glass (by means of double-exposure and optical printing techniques), was very common in Hollywood films of this period. It becomes obvious in the scenes set in Oz (where the landscapes are overtly stylised and illustrational), but the more deceptive views of Kansas were also simulated in this way.

Stories about the making of The Wizard of Oz have passed into Hollywood legend. But it’s true that the film that we know and love today could have looked and sounded very different…Did you know that Gale Sondegard the original actress chosen to portray the Wicked Witch of the West was something of a glamour-puss, and the designers’ original concept was reminiscent of the beautiful Evil Queen in Disney’s Snow White? When the executives eventually plumbed for the “hag” aesthetic, Sondegard pulled out and Margaret Hamilton was cast in her place. Did you also know that Judy Garland was not the MGM bosses’ original choice to play Dorothy but Shirley Temple—the pre-eminent child star of the day? It’s true that the song ‘Over the Rainbow’ was nearly cut from the film, because Louis B Mayor, the head of the studio thought that it slowed the pace of the action and set the wrong tone for Dorothy’s character. So there you go. With no rainbow and Shirley instead of Judy—would The Wizard of Oz have attained the popularity it holds today? Critics tend to believe otherwise.

The Wizard of Oz, 1939, dir. Victor Flemming (film still)

In fact however when it was finally released in November 1939, The Wizard of Oz failed to recoup the enormous amount of money that had been spent on the film (about 2 and half million dollars—a considerable amount in real terms). The film suffered from the loss of overseas revenue due to the outbreak of war in Europe. Nevertheless The Wizard of Oz did earn a popular following thanks to its musical score. Many of the songs from the film became hit songs and Judy Garland performed ‘Over the Rainbow’ repeatedly in her concerts for the American troops throughout the 1940s. In 1956 MGM sold the television rights for The Wizard of Oz to CBS making it the first American theatrical film to be shown complete in one sitting by a commercial network. Between 1959 and 1991 telecasts of the Wizard became an annual tradition drawing huge audiences in homes all over the US. And it was through this mode of dissemination that Oz achieved its iconic status. It is said that The Wizard of Oz has been by more people more times than any other film.

So what are the reasons for its popularity and its longevity? Why do people love the film so much and why do they go back to it again and again? Why does it hold up to repeated viewings? It is partly in attempt to answer this question that I’m going explore a couple of the themes that have helped to give the film mythological resonance, before proceeding to identify some of the writers and filmmakers that the film influenced among its legions of fans.

The Journey

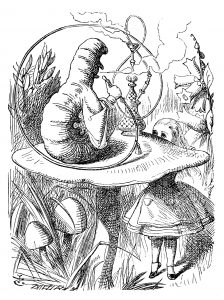

John Teniel, illustration to Alice in Wonderland, 1865

One of the central ideas that the Wizard of Oz explores is that of the journey both literal and metaphoric. The story makes use of a standard device in children’s literature: the notion of a (typically juvenile) protagonist from the real world who finds herself transported to and having to navigate a strange alternate reality. It’s known that Frank Baum, in writing Oz, was influenced by the novel which inaugurated this tradition in Western literature for children: Lewis Caroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, published in 1865. In many respects Dorothy is the American counterpart of the quintessentially English Alice; there are lots of obvious echoes between the two stories. One of important difference however concerns the nature of the journey undertaken by these two protagonists. Alice tends to wonder rather aimlessly in her fantasy world, encountering different characters and situations as they come along, and lacks a clear motivation. Dorothy, on the other hand, has the very definite goal of returning home, for which purpose she must seek the assistance of the Wizard; and her companions have explicit personal goals relating to the acquisition of intelligence, courage or whatever attributes they believe to be lacking. The goal-driven aspect of the story identifies it with the tradition of the quest narrative which has a very old vintage stretching back to ancient classical literature—the stories of Odysseus, or Jason and the Argonauts, for example. But the classical journey-myth that really resonates with The Wizard of Oz, on account of its female protagonist, is the Hellenistic tale of ‘Cupid and Psyche’ which we know from a literary version written by the Roman Scholar Apulius in the second century AD.

Eugène-Earnest Hillemacher, Psyche in the Underworld, 1865, oil on canvas, 117 x 90 cm, Melbourne, National Gallery of Victoria

This story, which has influenced numerous poets, artists and choreographers, concerns a mortal woman Psyche who becomes romantically involved with Cupid/ Eros, and has to undertake perilous journeys and various impossible tasks in order to prove herself worthy of her godly paramour. Pysche, like Dorothy, is assisted by various friendly characters she meets along the way in a series of episodic events that somewhat parallel Dorothy’s journey to the Emerald City and her subsequent quest to destroy the Witch of the West. Frank Baum may not have been directly aware of Apulius’s tale, but he was definitely aware of the folkloristic tradition it influenced. ‘Cupid and Psyche’ is the prototype version of stories that we now recognise as children’s literature, such as ‘Cinderella,’ ‘Snow White,’ and ‘Beauty and the Beast.’ The heroine’s name ‘Psyche’ resonates for a modern-day audience familiar with Freudian and psychoanalytic terminology—it’s a Latin term meaning ‘soul. This is an important aspect of the theme of the journey as it operates in The Wizard of Oz. In this type of narrative, the journey is more than a literal physical journey from one geographic location to another; it is always a metaphysical journey too; it concerns the psychological, spiritual and even moral development of the protagonist.

The particular form of psychological journey that the Wizard of Oz portrays is the journey from childhood to adulthood; this is accentuated in the film version through its portrayal of the central character. Judy Garland was sixteen when she undertook the role; she appears as an adolescent young woman in conflict with the older generation and torn between a longing to maintain the security of childhood and the inner-promptings that drive her towards adult autonomy and responsibility. One of the puzzling things about Dorothy’s journey (as many critics and fans have remarked), is that the ‘home’ to which she desperately wants to return is so unappealing—a site of considerable emotional conflict and strife. It would be important to mention that the archetype of the journey is an important one within American culture. Famous examples include Mark Twain’s picaresque novel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, published in 1884, Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, and the whole cinematic tradition of the ‘Road Movie’ (which includes everything from Easy Rider to Bonnie and Clyde and Thelma and Louise).

Is The Wizard of Oz a road movie? Yes of course it is. How else do we account for the importance of the ‘yellow brick road’ in the lyrics and narrative? Implicit in the tradition of the American picaresque narrative or ‘Road Movie’ is the protagonist’s ambivalent relationship to home and by extension to family, roots, ancestry and origins. This reflects the significance within American cultural identity of a relatively recent history of migration and displacement. The expansion of territory continued long after the Declaration of Independence, well into the nineteenth-century, and the age of the Western frontier, which informs so much of American mythology. These real-life memories and histories of displacement (many of them very traumatic of course) filter through stories like the Wizard of Oz— though not necessarily explicitly or consciously. The enduring popularity of the film resides in the fact that, no matter where we are in the world, no matter what our background is, we can relate to the experience of a conflicted relationship to home and origins. The tension between the need to stay and the desire to leave is something that many people experience in their lives; because of this the film continues to possess a great deal of resonance.

Dream Versus Reality

Dorothy’s journey crosses two worlds, a world defined in the film’s narrative economy as the ‘real’ world and a world defined as ‘imaginary’. We can relate this journey to the context of early-twentieth-century western-culture’s nascent love-affair with Sigmund Freud and his writings on dreams and the unconscious. Freud’s theories would influence not only the development of modern psychoanalysis and psychotherapy but also the strategies of manipulation used in advertising and consumer culture. Artists like Salvador Dalí investigated Freud’s theories in visual form. Major exhibitions of Surrealist art were held in New York in the mid-1930s, and Surrealist ideas were very quickly embraced by consumer culture in America—especially by the fashion industry and advertising. This helped to inform the cultural context in which Hollywood defined its fantasy worlds in visual form.

One obvious way that the distinction between fantasy and reality is drawn in The Wizard of Oz is in terms of colour (or the lack thereof). In many respects, this reverses our normal preconceptions. We would expect a full-colour image to be closer to reality because of its greater resemblance to how we perceive the world around us. However the use of black-and-white, or rather sepia film, in the sequences set in Kansas becomes the emotional shorthand for an oppressive quotidian reality. Dorothy’s Kansas is grey, or rather greyish-brown, because it is bleak, because it is mundane, because it is characterised by economic uncertainty even economic privation. It’s a very idealised view of agrarian poverty (as Salman Rushdie has remarked in his account of the film). Nevertheless the images of a colourless, drab, manifestly-joyless world have made sense to American filmgoers waiting for the Great Depression to end whilst anticipating the hardships and catastrophes that loomed as the 1930s drew to a close. What the initial use of monochrome also allows is the real experience of shock and wonder when Dorothy crosses over into Oz. We are able to experience her feelings of alienation, confusion and delight because the transition into full colour is so striking, so disorientating.

The Wizard of Oz, 1939, dir. Victor Flemming (film still)

It’s also important to acknowledge the overt theatricality of the film: the use of make-up and costume, the Victorian-style sleight-of-hand special effects, the overtly fabricated scenery, with its obviously-painted backdrops; the style of acting -so close to melodrama and vaudeville. Even the Hollywood musical has the effect of disrupting the transparency of cinematic illusion with the very self-consciously performative nature of song and dance. Because of this we are never quite allowed to suspend our disbelief. It’s almost as if we are meant to regard Oz as something of a fake—and this must have been true even for audiences in the late-1930s who were accustomed to, what we would now regard as, a primitive level of special-effects in cinema (there’s no way anyone would believe that the Cowardly Lion is ‘the real thing’—he’s very evidently a man in a lion suit etc.) At the same time however it’s possible to regard Dorothy’s journey as quintessentially cinematic—even symbolic of the metaphysical journey the viewer undertakes when watching the film. This is made clear in the scene when Dorothy, just prior to her arrival in Oz, looks out of the window of the moving house and sees images float past as they might on a cinema screen, thus occupying a role analogous to that of the audience itself.

Returning to Oz

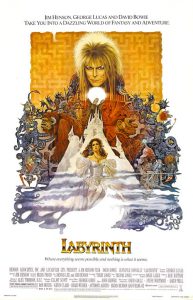

Labyrinth, 1986, dir. Jim Henson (theatrical poster)

Given that The Wizard of Oz is such a popular film, it’s not surprising that a number of remakes or revisionist versions have emerged over the years, ranging in quality and style. Among the most inventive is the 1974 all-black musical version starring Diana Ross and a young Michael Jackson. The Wiz relocates the story to 1970s Harlem and effectively urbanises the depiction of Oz itself—to the extent that the fantasy or fairy-tale elements of the story are played-down. This is perhaps endemic of Hollywood’s attitude to fantasy film in general. Possibly as a result of poor box office performance of The Wizard of Oz on its first release, ‘fantasy’ as a genre initially failed to take off in Hollywood. The sector became dominated by Walt Disney and either animated or partially-animated versions of children’s classics. Fantasy cinema did, however resurface in the 1980s, probably as a result of the success of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas with films made for a family audience. Many of the 1980s fantasy films look like unofficial remakes of The Wizard of Oz. The film Labyrinth (1986) which was directed by Jim Henson and written by ex-Python Terry Jones, is the story of a teenage girl from a late-twentieth-century American suburb who finds herself magically transported to a mythical world populated by variations of the Muppets and lorded over by the Goblin King, portrayed by David Bowie. Like Oz the film is a musical with all the numbers written and performed by Bowie himself. At the other end of the tonal scale, Disney released a sequel to The Wizard of Oz called Return to Oz in 1985 starring a young Canadian actress, Fairuza Balk as Dorothy. The film was hated by critics because it emphasised the dismal and frightening aspects of the story rather than the fun and vaudeville of the MGM version. But for many children who saw it on first release this has become a cult classic—and (film-buffs might be interested to note) this version was the only directorial work by Walter Murch, the sound editor on Apocalypse Now (1979).

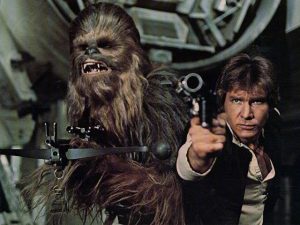

Star Wars: A New Hope, 1977, dir. George Lucas (film still)

Probably the most famous of the unofficial remakes of The Wizard of Oz is George Lucas’s Star Wars (1977). If you look at the line-up you’ll see that C3PO more-or-less resonates visually and tempermentally with the Tin Woodman, Chewbacca with the Cowardly Lion and the Evil Emperor with the Wicked Witch of the West. So where is Dorothy in the line-up? Has she been pushed into supporting role as Princess Leia or given a gender make-over as Luke Skywalker? You will probably remember that—like Dorothy—the hero of A New Hope (1977) is portrayed as an orphan raised on a farm by his aunt and uncle in a bleak landscape (in this case the desert planet of Tatooine) and undergoes a similar journey of psychological development via a road-movie/ quest narrative in space. Perhaps the most significant aspect of this particular remake is the negation of a female narrative perspective. The Wizard of Oz celebrates or at least acknowledges women’s power, not only in the person of Dorothy herself but also in the female authority figures who help to shape her journey into adulthood and responsibility. Watch out for Judy Garland’s reticent, slightly apologetic demeanour when she douses her nemesis—fatally—in water. Recall, too that the most obvious figure of patriarchal authority in the film—the Wizard— is such a ‘humbug’ (to quote the man himself). This idea explicitly informs Gregory McGuire’s revisionist novel Wicked (subsequently adapted for a broadway musical) which tells the story from the prespective of the Witch, placing her in the role of the sympathetic protagonist. The female protagonist of fantasy also comes to the fore in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, Tim Burton’s, aforementioned Alice in Wonderland (which says ‘Alice’ on the tin – but looks and sounds a lot like the Wizard of Oz) and del Torro’s Pan’s Labyrinth (in which another rebellious child seeks refuge from her oppressive sinister reality—in this case fascist Spain, just prior to the civil war—in a parallel fantasy world).

Perhaps the important characteristic that distinguishes del Torro’s film from most of the other remakes I’ve mentioned is the emphatically-invoked ‘mature’ audience—this is an important feature of our current vogue for the mythic and the magical. Indeed, the world of literary fiction, and writers as diverse as Angela Carter, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Margaret Atwood and Haruki Murakami have long understood that fairy tales are ‘not just for children’. Among the most famous and influential of the so-called ‘magic realist’ school of authors is Salman Rushdie the celebrated author of Midnight’s Children (1981) and the Satanic Verses (1988). Rushdie is a self-confessed Oz fan. As well as a short story based on the auction of the Ruby Slippers he also wrote the British Film Institute’s guide to the Wizard of Oz in 1992, and a novel called Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990) reinventing of Oz via aspects of Eastern mythology and modern-day Indian culture. Rushdie was raised in Bombay and makes interesting analogies between the Wizard of Oz and the hindi and early Bollywood films he saw in his childhood.

Wild at Heart, 1990, dir. David Lynch (film still)

The most controversial interpreter of Oz, is in many ways its most surprising aficionado. The American filmmaker David Lynch’s road movie Wild at Heart (1990) starring Laura Dern and Nicholas Cage includes a number of reference to the MGM classic: notably a cameo by Glinda the Good Witch, this time portrayed by the actress Sheryl Lee who also played the floating corpse of Laura Palmer in Twin Peaks (the television soap opera that Lynch co-created with Mark Frost). Lynch’s 2001 opus Mulholland Drive is another veiled remake. Consider the story of a naïve ordinary girl from a small town who journeys to a surreal metropolis (in this case a fictionalised LA / Hollywood), populated by a range of bizarre and sometimes grotesque characters (veritable witches and munchkins recast as studio personnel, drug-dealers and sinister vagrants). As in The Wizard of Oz it’s ambiguous as to whether the protagonist has dreamed the whole experience of this journey to another place; a further device that Lynch borrows from the 1939 Oz is that of doubling in the characterisation and performance (the use of the same actor to play two different roles), as a device to create echoes and transitions between the fantasy world and the notional world of ‘reality’. Lynch, of course, resides at the very place place where the ‘rainbow’ of Hollywood-imagination meets the Stygian river (the gate-way to the Underworld) of Greek mythology—but I mentioned him because I wanted to show the full range of diverse interpretations that The Wizard of Oz inspires. This for me demonstrates the extraordinary complexity of the film itself—that it can be read and enjoyed on so many levels. It’s a rare achievement in culture and must account for the film’s enduring popularity.

There’s No Place Like…

The Glasgow Britannia Panopticon

Finally I’m going to mention a little bit about today’s screening. We’re in the Britannia Panopticon which is Glasgow’s premiere music hall venue originally established in 1857. It’s very appropriate context aesthetically given the amount of vaudeville, conjuring and stage antics we’re going to watch in the film. However it’s also a testament to the city of Glasgow’s extraordinary cultural diversity and sense of history. Glasgow is a place fondly regarded and maintained as ‘home’ for generations, but also enriched by international links of trade and tourism, by immigrant populations and by scores of adventurers and journey-makers some of them ‘running away’ from home, like Dorothy, but perhaps—like Dorothy—also hoping to establish a new one. It tends to look rather more like grey Kansas than Technicolor Oz, owing to the weather conditions, but for many people Glasgow is a place as wonderful, as entertaining, as bizarre and sometimes as terrifying as the Oz portrayed on film, as anyone who’s experienced the N66 ‘night-bus’ will agree. With this in mind I’m going to conclude with Salman Rushdie’s thoughts on the theme of homeas it is explored in the film. He begins by describing the final scene:

Home again in black-and-white, with Auntie Em and Uncle Henry and the rude mechanicals clustered around her bed, Dorothy begins her second revolt…”It wasn’t a dream, it was a place,” she cries piteously. A real, truly live place! Doesn’t anyone believe me?”

Many, many people did believe her. Frank Baum’s readers believed her, and their interest in Oz led him to write thirteen further Oz books, admittedly of diminishing quality…Dorothy, ignoring the “lessons” of the ruby slippers, went back to Oz, in spite of the efforts of Kansas folk to have her dreams brainwashed out of her…; and in the sixth book of the series, she took Auntie Em and Uncle Henry with her, and they all settled down in Oz, where Dorothy became a princess.

So Oz finally became home; the imagined world became the actual world, as it does for us all, because the truth is that once we have left our childhood places and started to make up our lives, armed only with what we have and are, we understand that the real secret of the ruby slippers is not that “there’s no place like home,” but rather that there is no longer any such place as home: except of course, for the home we make, or the homes that are made for us, in Oz: which is anywhere and everywhere, except the place from which we begin.’ (Rushdie, 1992: 57).

This talk was delivered at the Glasgow Britannia Panoptican, 31st July 2012, as part of a special screening of The Wizard of Oz organised by Lorraine Wilson for The Merchant City Festival 2012.

REFERENCES

Rushdie, Salman. The Wizard of Oz. (London: British Film Institute, 1992).