Jan 22

2018Anachronism, Art History, Contemporary Visual Art, Fairy Tales, Writing as Creative Practice

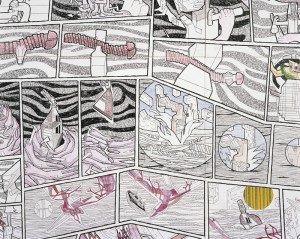

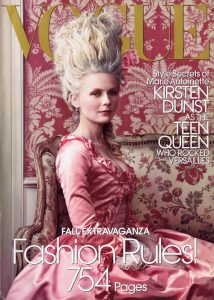

Bad Retail: A Romantic Fiction (preamble)

[…] these quilted snatches are viewed as past moments – of clarity, beauty, civilization, and spiritual elation – that must somehow be retained and restitched in a sense, spliced onto the present, […] as if they were alive, as if they were types of intelligent, deathless energy, and this so as to allow the past, with a nourishing insistence, to feed the present.

(Oppenheimer 1998: 84, ‘Goethe and modernism’) Read more →