Lotte Gertz: New Work

Gertz’s latest series of paintings and prints were made in a studio that occupied the same space as her general living-area and are full of the sense of immediacy that results from an artist’s direct response to ‘close-at-hand’ materials and objects.

Gertz’s sources include those items she ‘stumbles-upon’ again and again in the intimate chaos that surrounds her as she works: a space where ‘living’ encroaches upon ‘making’, where discarded playthings (a stuffed panda-toy or a wooden Pinocchio-figure) might be found side-by-side with DIY tools, painting and printmaking materials, half-eaten slices of fruit or cheese, still-to-be-drunk cups of tea, and photographs of famous artworks from books and magazines.

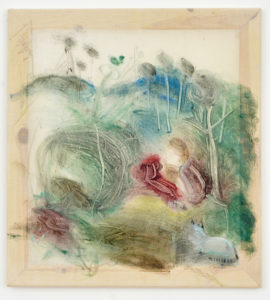

Lotte Gertz, Wilderness or how her stubbornness went far but not far enough to change the face of the mountain, 2012, oil paint on muslin 56 x 51 cm, © Lotte Gertz

A sense of the lowly – perhaps even the vaguely sordid – is embodied in the physical construction of the works themselves which include several paintings on muslin. The latter is itself a simultaneous nod to functionality and preciousness: the life-blood of BBC costume dramas, the fabric —in its pale refinement—seems to await a scatological sort of contamination. When stretched and sized, it becomes a kind of ‘canvas’, and the marks added to its surface in rapid layers and impressions capture, in their viscous beauty, the excitement of Gertz’s continual (re)discovery and material (re)invention of objects both familiar and strange.

The Roman scholar, Pliny the Elder used the term rhyparographos from the word rhyparos (meaning ‘waste material’) to denote an artist engaged in representing ‘insignificant’ or day-to-day subjects (‘still-lives’ and ‘genre’ paintings as they would later come to be known in art-historical terminology) (qtd. Bryson, 1990: 136). As the scholar of still-life Norman Bryson acknowledges, the painting of the ‘mundane’ is ‘negative only from a certain viewpoint, in which the ‘lowness’ of a supposedly low-plane reality poses a threat to another level of culture that regards itself as having access to superior or exalted modes of experience’ (Bryson, 1990: 136).

Gertz’s practice, on the other hand, reflects a contemporary epoch in which the exalted and the mundane, the megalographic and rhyparographic, become intermingled and confused (a consequence perhaps of the rapid dissimilation of images through photographic and digital reproduction). Gertz’s working-environment (like many artists’ studios) is a place where the facsimiles of old masters—the objects of ‘superior and exalted experience’—are scattered through the general transient clutter. Her studio is full of the magpie souvenirs of contemporary tourism, internet surfing and ‘charity-shopping’: postcards, print-outs, second-hand book-pages and the like.

Gertz’s paintings and prints are born of a creative context in which a revered canon of images and what Bryson calls the ‘basic routines of self-maintenance’—cooking, eating and shopping—are jumbled up and deprived of their respective places in the cultural hierarchy (Bryson, 1990: 137). Whilst possessing an air of the lowly, the insignificant and the day-to-day, the works embody, at the same time, shades of the mythological and the iconic. It would be misleading to describe Gertz’s recent works as ‘still-lives’—there are ‘history paintings’ and ‘landscapes’ too among her recent body of paintings as well as images reminiscent (in their regulated motif patterning) of wall-paper and poster design. But the references are not fixed in Gertz’ flowing, partially-abstract compositions; the viewer is compelled to speculate over the faint traces of ‘annunciations’, ‘temptations’ and other Biblical scenes visible in some of the paintings.

Lotte Gertz, Group of galloping hammers, 2012, oil & acrylic paint on muslin, 56 x 51 cm, © Lotte Gertz

The ambiguity and flexibility of Gertz’s visual representations are furthered by the sometimes wordy cryptic titling derived from fiction, poetry or Gertz’s own coined imaginative phrases. Some of the titles bare a straightforward relation to the images in question; others are divorced from their original literary contexts and appear to negotiate new meanings in relation to the art-works they now label. The titles also mix abstract and concrete nouns in such a way that the metaphysical concepts they describe seem crystalized as physical entities. This aspect resonates in turn with the feeling of transformation in the works themselves. Many of the paintings start off as mono-prints, gestural images sketched out in thick paint on Perspex to which sheets of paper or fabric are applied (before being worked-into with brushes or other tools). In the finished paintings the medium still appears in the throes of transformation into a discernible representational form. This simulated change is not quite solidified and therefore open to a feeling of movement or discovery, and as such relates to the idea of the rhyparograph as a document of daily life. Waste, production, consumption, decay are themes inherent in the idea of mundane lived experience; all are processes characterised by transition, metamorphosis, and a continual shift in material states.

Closely related to these ideas of entropy and change is the notion of quotidian objects as ephemeral sorts of souvenirs. Just as mono-printing acts as a kind of record or ‘memory’ of an image lost when the plate is wiped clean, a domestic space is—like the studio—a space of absolute impermanence. Here the past is only briefly preserved in the form of objects which bear—in their scuff-marks and blemishes—the traces of their intimate usage, until they vanish in their obsolescence—thrown-out with the trash or painted-over. The following passage from Margaret Atwood’s novel The Blind Assassin (2000) reminds us of the equivalent fragility of the photograph as memorial object (at least in its traditional printed form—we have yet to know how we will regard the digital photograph in posterity). But Atwood’s description might also afford an appropriate epitaph for Gertz’s oneiric—almost recognisable—images of figures, objects and scenes:

She retrieves the brown envelope when she’s alone, and slides the photo out…She lies it flat on the table and stares down into it, as if she’s peering into a well or pool – searching beyond her own reflection for something else, something she must have dropped or lost, out of reach but still visible, shimmering like a jewel on the sand. She examines every detail…The trace of a blown cloud in the brilliant sky, like ice cream smudged on chrome. His smoke-stained fingers. The distant glint of water. All drowned now. Drowned but shining. (Atwood, 2001: 8)

References:

Atwood, Margaret, The Blind Assassin, London: Virago Press, 2001.

Bryson, Norman, Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting, London: Reaktion Books, 1990.

This essay was commissioned for the exhibition ‘Lotte Gertz: New Work’, Mary Mary Gallery, Glasgow, 8 June – 4 August 2012