The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods: A Surrealist Awakening

Gustave Doré, Illustration for Charles Perrault’s ‘La Belle au Bois Dormant’ in Les Contes de Perrault (one of six engravings), 1867.

André Breton did not have an unalloyed respect for fairy tales. He found them ‘puerile’ and conformist; in his view, these stories were ‘addressed to children’, and, as such, could not substantially influence the adult mind with their fantastic visions (Breton, 2010: 15). He held out hope that fairy tales could be ‘written for adults, fairy tales still almost blue’ (Breton, 2010: 16).

In the 100 years since Breton made this statement, fairy tales ‘for adults’ have become much more prominent—and their relationship to ‘Surrealism’ much more tangible. In her book From the Beast to the Blonde (1994), the writer and critic Marina Warner acknowledged the vexed relationship of these two genres of ‘the fantastic’. She gives special emphasis to women artists connected with the movement (such as Leonora Carrington and Meret Oppenheim), whom she regards as modern fairy tale ‘tellers’ (see Warner, 1994: 384-5).

My own creative practice emphasises the role of visual material in shaping our experience of these contradictions. I am a painter and writer who has lived in Glasgow for more than twenty-five years. My ongoing interest in fairy tales and Surrealism has been nourished by that context—notably through dialogue with the Scottish writer and art historian, Catriona McAra, who has written extensively on these subjects. As McAra has shown, through her perceptive analysis of the work of Tanning and Carrington, the ‘surrealist fairy tale’ is a hybrid genre that subverts the reader’s (or the viewer’s) expectations, bringing about a contradictory relation of ‘text’ and ‘image’.

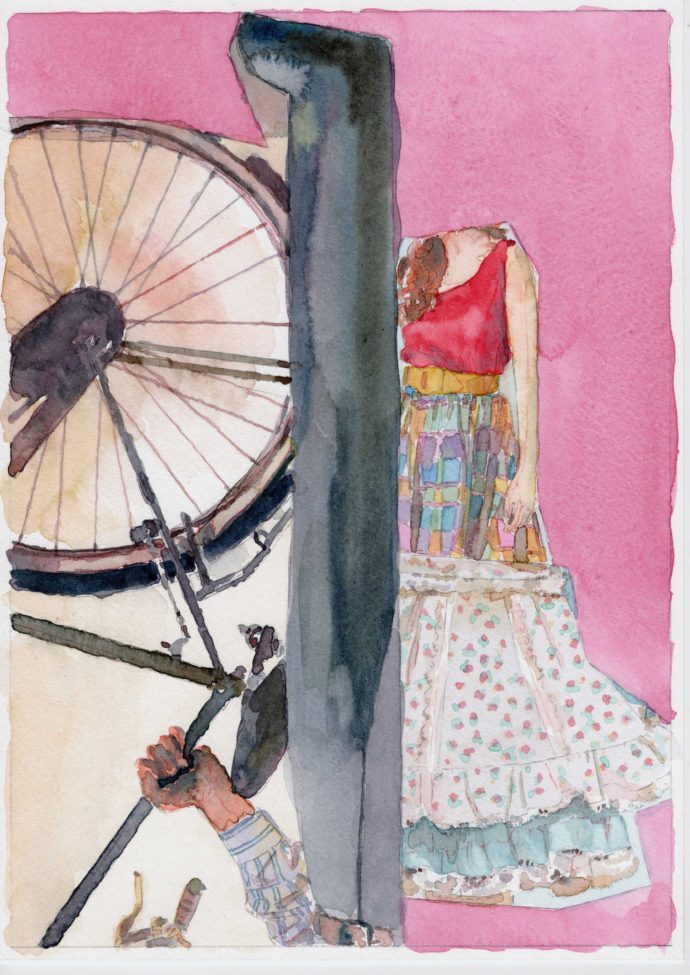

In the summer of 2024, I began making a series of 26 illustrations to ‘La Belle au Bois Dormant’ the frequently censored baroque version of the story more commonly known as ‘Sleeping Beauty’ (first published in 1697). Intended for both an exhibition and an artist book, these works stage a material encounter of surrealist aesthetics and the literary fairy tale. Taking the form of watercolour paintings derived from 1980s-era magazine-pages and film-stills, these images are counterpoised to a well-known story.

***

The brainchild of Charles Perrault—a French civil-servant and philosopher, who had served at the court of Louis XIV and participated in the ‘Quarrel of Ancients and Moderns’— ‘La Belle au Bois Dormant’ (‘The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods’), played a key role in the imperfect historical process of ‘civilising’ fairy tales. According to the Marxist folklorist, Jack Zipes, this was not a straightforward process; fairy tales were not always ‘approved for children’:

[…] they were so symbolic and could be read on so many different levels that they were considered somewhat dangerous: social behaviour could not be totally dictated, prescribed, and controlled through the fairy tale, and there were subversive features in language and theme. (Zipes,1995: 25)

Indeed, the story of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ (as told by Perrault) proves to be surprisingly ‘adult’ and ‘subversive’ in its ‘language and theme’. In Perrault’s rendition, we are told, the Sleeping Beauty has ‘the pleasure of very charming dreams during her long slumber’; when she wakes, she is able to hold the prince in erudite conversation (Perrault, 1991: 48). This makes sense from a Surrealist perspective. As Warner writes, echoing The Surrealist Manifesto, ‘dreaming gives pleasure in its own right’ but ‘also represents a practical dimension to the imagination, an aspect of the faculty of thought, and can unlock social and public possibilities’ (Warner, 1994: xvi).

The suggestive pricking of the spindle (a rupture— like the incision of collage in surrealist or modernist picture-making) cracks open the fabric of reality, suspends the patriarchal social order and disrupts chronological time. Out of this wound leaks a horror story (reminiscent of the gothic novels that enchanted Breton)—the Sleeping Beauty, in this version, wakens into a nightmare. The prince’s mother is an ogress, who wants to eat the princess and her young children – served with a delicious French sauce. After she is herself devoured (in a cauldron filled with ‘toads, adders and serpents’), the prince sheds a tear: he ‘could not help but feel sorry,’ Perrault concludes, ‘for she was his mother, but he speedily consoled himself in the company of his beautiful wife and children’ (Perrault, 1991: 51).

***

My response to the tale is shaped by an intuitive understanding that these (rather mawkish) images (of devouring, piercing and dreaming) lend themselves to Surrealist interpretation, perhaps especially to the language of collage (a favoured Surrealist technique). The methods I used to illustrate the story were closely informed by Hal Foster’s analysis of Max Ernst’s collage novel, Une Semaine de Bonté (1934), a famous work of Surrealism. As Foster observes (in his book Compulsive Beauty, 1993), Ernst’s process of cutting and re-assemblage ‘articulates’ the psychological and political content repressed in his source material:

Many of the sources are overtly melodramatic. Several images in Une Semaine de Bonté are based on Jules Marey illustrations for Les Damnées de Paris, an 1883 novel of murder and mayhem. These illustrations depict drames de passion […] In his appropriation Ernst relocates these particular scenes in psychic reality through the substitution of surrealist figures of the unconscious […] (Foster, 1997: 177)

Following Ernst’s use of 1880’s book engravings (that were 40-50 years out of date when he appropriated them for his collage-novel), I made use of images dating from my own childhood—from the last two decades of the twentieth century. This approach constitutes an apt vehicle for Perrault’s enchanted princess, who (waking from a hundred-year sleep), is herself a form of anachronism. As Lewis C. Seifert has written in his essay ‘Queer Time in Charles Perrault’s “Sleeping Beauty”’ (2015): ‘By deviating from the ordered sequence of chrononormative time’ the story opens a space for ‘other ways of being and desiring’ (Seifert, 2015: 24).

There are no spindles or thorns in this depiction of the story; instead, shiny corporate artifacts and ‘white-collar’ fashions of the 1980s (emerging in such sources as Dynasty, Playgirl, and Vogue), replace the ancien-regime symbols of the original. These postmodern images are, for me, expressive of what Foucault named the ‘administrative grotesque’ (albeit in a more glamorous form). ‘The grotesque,’ he stated, in his lecture Abnormal (1974), ‘is a process inherent to assiduous bureaucracy’ (and its effective abuse of power) (Foucault, 2003:13).

What the meaning of this language might be (arising as a visual response to ‘Sleeping Beauty’), remains enigmatic—a site of tonal and aesthetic discordance. (We readily attribute the grotesque to fairy tales, but the language of ‘administration’ has been claimed by Orwell, Kafka and the dystopian fictions they inspire.) Further analysis will reveal whether this particular re-imagining of the story constitutes an eccentric anomaly or whether it substantively illuminates the political significance of Perrault’s tale. In the meantime, these none-sequiturs are welcome, arising from my intention to utilise the chance methods of Surrealism as expansive forms of fairy tale illustration, to observe what ‘spaces for imagining’ arise from this interpretive method.

Laurence Figgis, 2025

This paper was delivered for the ‘Art & Text Conference’, Scottish Society for Art History, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, 7th February 2025.

References

Breton, A. (2010), Manifestoes of Surrealism. trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane, 5th ed., (Michigan: University of Michigan Press).

Foster, H. (1997), Compulsive Beauty, 3rd ed., (Cambridge: Mass.; London: MIT Press).

Foucault, M. (2003), Abnormal: Lectures at the College de France 1974 – 1975, ed. Velerio Marchetti and Antonella Solomoni, trans. Graham Burchell, New York: Picador.

Perrault, C. (1991), ‘The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods,’ in Beauties Beasts and Enchantment: Classic French Fairy Tales. ed. and trans. Jack Zipes (London; New York: Meridian), pp. 44-51.

Seifert, L. C. (2015), ‘Queer Time in Charles Perrault’s “Sleeping Beauty”’, Marvels & Tales, Vol.29 No.1, 21-41.

Warner, M. (1994), From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers. (London: Chatto and Windus).

Zipes, J. (1995), ‘Breaking the Disney Spell’, in From Mouse to Mermaid, the Politics of Film, Gender and Culture, ed. Elizabeth Bell, Lynda Haas, and Laura Sells, (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press): 21-42.

Laurence Figgis, “she entered a little garret, where an honest old woman was sitting by herself with her distaff and spindle,” (illustration to La Belle au Bois Dormant), 2024, watercolour on paper, 297 x 207 mm Laurence Figgis.