Divine Hangers: On the Critical Rigour of the Q-Q

They are lifeless lay figures pulled about by wire; they are cleverly put together, but the wood and the steel skeletons support merely stuffed puppets with whom the author deals most cruelly, jerking them into the strangest poses, contorting them…cutting up their bodies and souls – but because they have no flesh and blood all he can do is tear up the rags out of which they are made; all this is done with considerable historical and rhetorical talent and a vivid imagination; without these qualities he could not have produced these abominations. (qtd. Lukács, 1978: 94)

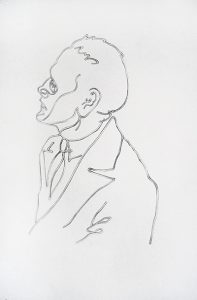

Goethe

Clare Stephenson, Genet Portrait, 2003, pencil on paper, 43.5 x 32 cm, © Clare Stephenson

Lukács, sceptical of the extent to which Zola had adhered to the ‘scientific’ model in the realisation of his greatest fictions ultimately welcomed the failure. The ‘scientific” method’, he insisted, ‘always seeks the average, and this grey statistical mean, the point at which all internal contradictions are blunted, spells the doom of great literature’ (Lukács, 1978: 91). Nevertheless he called it “a strange element of tragedy’ that ‘Zola, who criticised so vehemently the romantic lapses of his peers, could only escape the counter artistic consequences’ of his own dogma through a romanticism of the ‘Victor Hugo stamp’ (Lukács, 1978: 91).

Such conflicts are not exclusive to nineteenth-century literary naturalism. The artist Clare Stephenson illuminates a comparable ironic condition in her drawings, sculptures and spray paintings; an analogy of the more hysterical proponents of the Hollywood ‘method’ who tend towards a preposterous excess of ‘research’ and a rather too-stylised grittiness. La technique refers, in her idiom to a peculiarly specialised process involving the meticulous drawing of unravelled coat hangers in various fictional contortions, including a self-promoting caption and the traced contours of Jean Genet (in a drawing after Cocteau). It would appear that Stephenson regards not naturalism, but a pedantically over-structured vacuousness as the current dogma of visual practice and aims to satirise its forms through mimicry; incorporating over-worked formal strategies, slapstick historicism and the substitution of empty Euro-centric brand names for critical or practical terminology.

The objects portrayed in the drawings are as much informed by problems of support, weight, and balance as if they were blueprints for sculpture; the acknowledgement of ‘material consequence’ ensuring against the ‘crappy formalism’ of random pictorial motifs. It would be misleading however to speak of a simple binary opposition of comical and formally engaged elements in Stephenson’s work. The latter edify the former, revealing caricature itself to be a historically grounded aesthetic category.

Clare Stephenson, La Caricature, 2004, pencil and aerosol paint on paper, 55 x 59.5 cm, © Clare Stephenson

With their piggy eyes and inflated quiffs of powdered pompous hair, Daumier’s Lecomte, Sébastiani and Kératry are the gnomes of legislative power whose 21st century counterparts continue to warrant a dressing down. But the specific and the general targets of Daumier’s savage stylus are somewhat muted by Stephenson’s predilection for the raddled image of sculpture as a work-in-progress, suggesting that what is under analysis is not the evil of July-Monarchist (or New Labour) bureaucrats but the very concept of caricature itself as a form and a discipline.

Parody is revealed as a complex process of mimicry and transformation, which exploits the humorous potential of cultural quotation and displacement, eliding from an obtuse patchwork of decorative signs. Stephenson’s sleight-of-hand is to preserve the sculptural integrity of her sources while ironically transplanting them, a recurrent solution being to gather several images into a portmanteau form ostensibly made of clay, supported by a tenuous makeshift armature. The use of metamorphosis and double-reading, of the sort seen in Arcimboldo’s painting of capriccio fish and vegetable heads, considerably furthers the imaginative and satirical power of her ‘abominations’, notably in Wigs in which the double helix —the current essentialist metaphor par-excellence—is rendered ludicrous as the conduit of bulbous falsities.

Clare Stephenson, The Quite Quite, 2003, Jelutong wood and gouache, 14 x 15 x 8 cm, © Clare Stephenson

Such lumpy rhetorical phenomena belong in the spurious tradition of the ‘heavy electricity’ described in Chris Morris’s Brass Eye lampoon. At the same time they are physically believable, the coherence and precision of the drawing suggesting both a scientific and a prototypic function. The determinist fantasies they incite are however pointedly defeated when an actual sculptural work appears in the wings—as it did in the recent solo show at Transmission. The Quite- Quite is Stephenson’s homage to the absurdly contracted patois of Divine and Mimosa, the drag-queens in Jean Genet’s Notre-Dame des Fleurs, who in moments of distress, to avoid “an exuberance of gesture or voice’, content themselves with saying: ‘“I’m the Quite-Quite”’, – and subsequently, ‘“I’m the Q-Q” – in a confidential tone’ (Genet, 1963: 121-1). Stephenson’s rather modest yet suggestively totemic caption is a ‘pre-existent object’ still emerging from the carved block of its own substance like one of Michelangelo’s half-formed slaves; it attains final comprehension via a cigarette adroitly dissecting the o-shape of its implied mouth to form a ‘Q’. The Quite-Quite is for Stephenson ‘an object without content’ made of ‘vagaries and affectation’. At Transmission it was the only sculpture-proper among a whole host of sarcastic little monuments represented in two-dimensional form, and as an acerbic addenda to her represented oeuvre, fulfilled a wry and critically schizophrenic function.

Clare Stephenson, La Technique, 2003, pencil and aerosol paint on paper, 59 x 84 cm, © Clare Stephenson

Stephenson has spoken of her work in terms of the ‘caricatures you make of yourself making different kinds of work’. The term self-satire is critically occlusive, the model in question being a mere example of tendencies, a straw—or wire—target contrived to illuminate both the foibles of a rhetorical practice and its subversive potential. Thus on the one hand we could speak of an ethically imperious Hollywood star whose ‘real-life’ allusions are strategically placed; on the other, of a drag queen out of John Waters or Jean Genet, whose ‘vagueries and affectation’ amount to a brittle sort of dogma. It is just such a doubled figure who hovers behind the emphatic tumbleweeds of La Technique, whose voice can clearly be inferred, sardonically intoning: as a coat hanger I was armature. Now I am sculpture. I was throw away; now I am purity of form, grace of line. Formerly capitalist detritus; I am poetry. I was fashion; I am art.

References

Genet, Jean, Our Lady of the Flowers, New York: Grove Press: 1963

Lukács, Georg, Studies in European Realism, London: The Merlin Press, 1978

This essay was originally published in Clare Stephenson, (Glasgow: Transmission Gallery, 2004): catalogue produced to accompany the exhibition, ‘Clare Stephenson’, at Transmission Gallery, Glasgow, 5 June – 3 July 2004