Anachronistic Pursuits: In Conversation with Catriona McAra

For over a decade, Laurence Figgis and Catriona McAra have shared an interest in the anachronistic union, and narrative possibilities, of Surrealism and the fairy tale. The most recent manifestation was ‘(After) After’ (2017), a solo exhibition by Figgis curated by McAra with an accompanying critical text by Susannah Thompson. ‘(After) After’ suggested an extension to the surrealist story, the need to find out what happens after the “happily ever after” of the movement. The exhibition made numerous references to surrealist techniques (word play, collage and metamorphosis). This in-conversation positions Figgis’s long-term critique of the kitschification of surrealism within the Scottish cultural landscape where he has forged his artistic career.

CM: I’m excited to be in conversation with Laurence Figgis, a Glasgow-based contemporary artist whose practice I’ve been very interested in for about 13 years now. We became friends when we were both studying surrealism at the University of Glasgow and have maintained a dialogue ever after. In 2017 I was fortunate to be able to invite Laurie to show with me in the gallery I used to run at Leeds College of Art, and the result was an exhibition ‘(After) After‘ a very playful show of recent narrative paintings that focused on the idea of anachronism. Laurie’s visual quotation included avant-garde icons such as Robert Rauschenberg ‘s collages and Picasso’s own quotation of Velásquez among many others. And I should add that Professor Susannah Thompson was invited to write a very interesting text for that show. Prior to the Leeds show, Laurie has had further solo shows including ‘The Great McGuffin’ at Transmission in 2005 and ‘Hugs N Fun Fun’ at the Glasgow Project Room in 2013.

So hello Laurie! It’s great to be speaking with you at this event. I would like to open the conversation by thinking about the place of Surrealism in Glasgow, and I want to delve a little deeper than Dali’s Christ of St John on the Cross…

I’ve long been struck by the polarisation of the Glasgow art scene as discussed in Sarah Lowndes’s book Social Sculpture (2010). A real sense of the generational, ideological tension seems to have occurred between the figurative painters in the 1980s (Ken Currie, Steven Campbell et al) and the neo-conceptual art that came to dominate the international prize networks by the mid 1990s (Christine Borland and Douglas Gordon for example). Such conceptual art practices are heavily reliant on the readymade precedents of Marcel Duchamp. Borland and Gordon stem from the Environmental art course at Glasgow School of Art (so it is probably worth considering that GSA pedagogy within this conversation) and both utilise juxtaposition, wordplay and found objects, absurdist tales and borrowed film footage, but such practices seem to have paved the way for something else.

I’m interested in the next generation after that, mine and yours, ours, what I perceive to be a particular moment in the late 1990s and early noughts in art education when aspects of both the figurative and the conceptual begin to gel into something else. A few Glasgow-based artists (all artists born around 1975-1979), including yourself, start reintroducing narrative, figurative content back into advanced aesthetic thinking. We see this too in the painting of Lucy McKenzie and in the sculptural work of Clare Stephenson. I am personally very drawn to the work of Lucy Skaer and her own oblique take on art history and her iconoclastic questioning of the status of the image. This oblique or anamorphic mode of perspective as scholar Kate Conley calls it in surrealism might actually be a useful way of thinking about the theme of Surrealism in Scotland.

I curated an exhibition of Skaer’s work in 2016 (the year before your show in the same space), and I was especially interested in how her work can be seen to reply to Leonora Carrington both before and after her death. Here we see Carrington’s Memory Tower of 1995 next to Skaer’s Harlequin is as Harlequin Does (2012), a ghostly screen print of a photograph taken outside of Carrington’s home in Mexico City after the death of the artist.

Can you talk about what role Surrealism as an art movement or philosophy might have played in this reintroduction of figurative content or a different way of practicing in the millennial years and beyond?

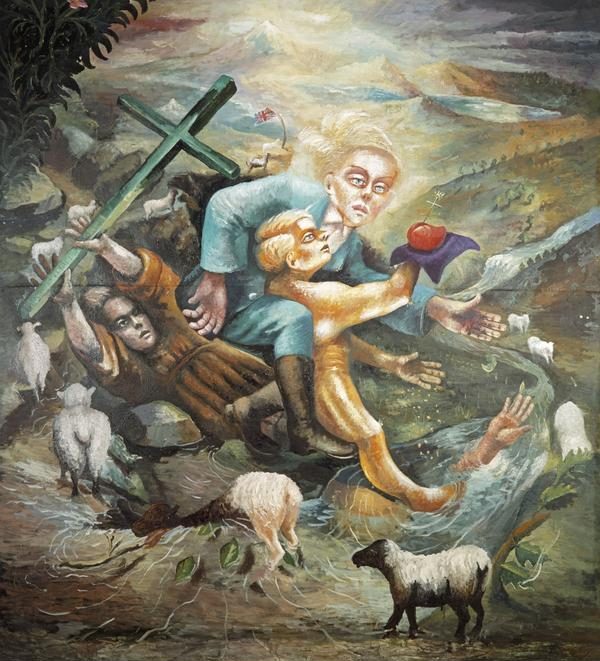

Steven Campbell, Elegant Gestures of the Drowned after Max Ernst, 1986, oil on canvas, 262 x 238.4 cm, Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland

LF: The answer to that question is complex because of the diffusive nature of surrealist influence on art and culture since the 1920s. In my paper for the ‘Surrealism and Scotland’ panel for the Association of Art Historians conference last spring, I talked about the taxonomic confusion that occurs when trying to categorise the work of artists emerging in Glasgow in the early noughts. It’s definitely true that following a period in which neo-conceptual approaches seemed to dominate the Glasgow art scene, there was a turn to metamorphic imagery (for example in the paintings of Alex Pollard, who represented Scotland at the Venice Biennale in 2005), the use of collage and the use of the objet-trouvé as a psychologically-charged device (for example in the sculptures and installations of Cathy Wilkes). While we can relate all of these formal strategies to Surrealism, it’s not often clear whether the artists in question are drawing direct influence from the surrealist movement as defined by André Breton in 1924; or from historical movements that inspired Surrealism such as Symbolism and Art Nouveau; or from post-modernist artists of the 1980s, such as Steven Campbell who had been one of the most successful painters to emerge from Glasgow in the previous decades. It’s also true that artists of my generation grew up with a range of pop-cultural media that had plundered surrealist devices without necessarily being faithful to or cognisant of the specific intellectual and political ambitions of Breton’s Surrealism. Finally, I think with regard to Glasgow, there is something about the city which lends itself to artists prioritising what Louis Aragon called a sense of ‘contradiction within the real’ (Aragon, 1994: 217). This sensibility is felt in the varied architecture of the city (which produces a dream like collage), the prevalence of urban decay alongside grandeur, and in the tangible influence of celtic mythology and gothic aesthetics on its most famous heritage sites. In short it seems like the kind of city that the Surrealists would have enjoyed getting lost in. Perhaps the lasting tribute to this particular form of ‘convulsive beauty’ is the Charles Rennie Mackintosh building at the Glasgow School of Art (where I studied). Here we have an example of the kind of architecture Salvador Dalí might have admired; if we read Dalí’s description of Gaudí’s architecture, in his writing on Art Nouveau, it would fit nicely with the aesthetics of Mackintosh and the ‘Spook School’ more broadly.

CM: So, what you’ve touched on there is that Surrealism has a pop cultural appeal, an aspect which has peaked and troughed throughout the twentieth century. When I was starting out working on feminist-surrealist visual narratives around 2007, it wasn’t always viewed as very trendy! I’ve witnessed a very different uptake over the last decade so it is more legitimate to be interested in artists like English-speaking surrealist artists like Carrington and Tanning now that they have had big solo shows at Tate Modern and the Museum of Modern Art in Mexico City. They have become more acceptable and (dare I say it?) canonical while retaining some of their edginess and cult following. Carrington’s Milk of Dreams is even the theme for this year’s Venice Biennale! At Tate Liverpool, Carrington’s show, ‘transgressing discipline’ was interestingly placed alongside a sister exhibition by Cathy Wilkes exploring the overturning of domesticity… Could you say something about how pop and surrealist aesthetics informed your work for the exhibition ‘(After) After’ and some of your more recent work over the last five years perhaps?

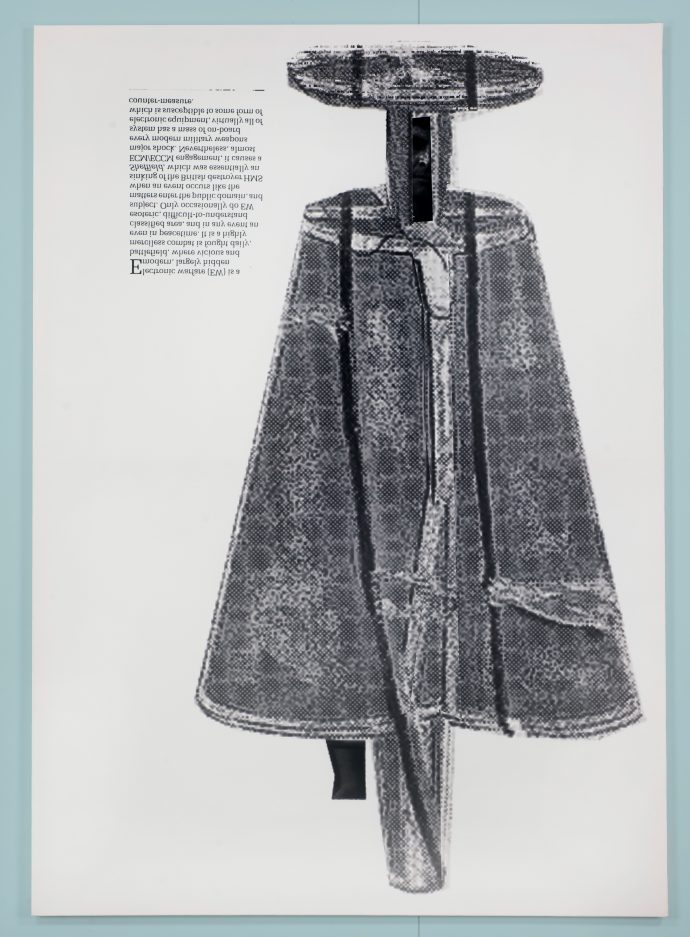

Laurence Figgis, The General, 2017, dye-sublimation print on canvas, 200 x 141 cm, ©Laurence Figgis

LF: An example of this would be the work entitled The General which was one of the larger pieces shown for ‘(After) After’. The work is a dye sublimation print on canvas. Part of the image derives from a work of art that was admired by the Surrealists especially by Andre Breton: Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass or The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors (Even) (1915-23). My collage was inspired by the design of the so called moules malic (the masculine component of the imaginary desire machine depicted in The Large Glass). I had always been intrigued Duchamp’s reference to uniforms and liveries in his famous notes to the work. I wanted to accentuate this reference; so, by use of digital compositing, removed one of the uniform-like figures from a photocopied detail of The Large Glass and used it to clothe or cover the figure of a male nude derived from a 1970s edition of Playgirl magazine. This composite image was printed human size on a canvas, at which point I was surprised by its sinister resemblance to Darth Vadar… In summary, this work combines three artistic traditions; firstly, the idea of appropriating from art history (through printmaking), a process very much associated with Pop Art and Andy Warhol; secondly the use of this idiom to create a surrealist atmosphere of psychological and erotic tension; and thirdly the use of this method to make visual links with cinematic genres of fantasy and science fiction that are often tangentially aligned with surrealist art and literature.

CM: Interesting that you raise the theme of masculinity and gender. My own work has often focused on feminist, and increasingly intersectional, readings of the surrealist movement, so very historiographical concerns with the scholarship and how artists are represented in subsequent critical writing. The English artist Angela Carter had much to say about surrealism and what it meant for her as a woman:

‘When I realised that surrealist art did not recognise I had my own rights to liberty and love as an autonomous being, not as a projected image, I got bored and wandered away‘ (Carter, 1992: 67)’.

There has also been an ongoing manifestation of queer aesthetics (beginning with Jean Cocteau) which echoes or mobilises surrealist strategies. Again, with reference to the work shown in ‘(After) After’ (and more recent work), could you say something about how politics of gender and sexuality might be implicated in the contemporary use of a surrealist aesthetic?

Simone Leigh, Las Meninas, 2019, terracotta, Steel, raffia, porcelain, 182.9 x 213.4 x 152.4 cm, The Cleveland Museum of Art

LF: When it comes to my own engagement with themes of gender, class and sexual politics, in the work produced for ‘(After) After’ and beyond, this occurred via a methodology of anachronism (as a mode of picture-making). The idea of mixing up different time periods, of allowing the image of the past to challenge the (assumed) progress of modernity, is an important strategy of Surrealism, as seen in the collage novels of Max Ernst. However, this is also a characteristic that led the movement to be discredited by Clement Greenberg and others for being insufficiently modernist. I’ve become interested in recent artists who’ve engaged with anachronism as a methodology in relation to images of gender, class and racial politics. This imagery has obvious subversive and humorous potential with regard to contemporary class politics, celebrity culture and so forth. And similar strategies have been deployed by artists engaging with social justice themes: for example, Kara Walker, who, since the 1990s, has been using collage to subvert romanticised imagery of the nineteenth-century antebellum south from a contemporary black-feminist perspective. Recently I’ve become interested in the work of Simone Leigh, an American sculptor who reinvented the figures of Las Meninas (after Velásquez), using motifs and materials inspired by diasporic Afro-Brazilian religious rituals. I think the lesson learned from these works is that the methodologies of Surrealism are often ambiguous…

My own body of work has definitely been inspired by the scholar of French literature, Lewis C. Seifert, who argues for a positive view of anachronism in their discussion of the story of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ by Charles Perrault. Writing in relation to the spectre of frozen time embodied in Perrault’s seventeenth-century fairy tale, Seifert argues that:

‘…queerness frequently pulls the past into the present because it is so often experienced—and portrayed—as a […] belatedness, pause or delay in the trajectory towards the normative goal of heterosexuality (Seifert, 2015: 27)‘.

Citing the queer philosopher of time, Elizabeth Freeman, Seifert proposes a queer-affirmative use of ‘this lingering of pastness by artists, writers, and critics who “put the past into meaningful and transformative relation with the present”’.

Works cited:

Louis Aragon, Paris Peasant, trans. Simon Watson Taylor, Boston: Exact Change, 1994): 217.

Angela Carter, ‘The Alchemy of the Word’ in Expletives Deleted: Selected Writings, 67-73. London: Vintage, 1992.

Lewis C. Seifert, ‘Queer Time in Charles Perrault’s “Sleeping Beauty”, Marvels & Tales, Vol.29 No.1 (2015), 21-41