The Sentimental-Sublime

In the autumn of 1927, Salvador Dalí wrote to his friend Frederico Lorca denouncing the much-admired contemporary Spanish poet, Juan Jiménez. The latter, according to Dalí, is a ‘putrid marasmus’ who ‘has never ever seen anything, only receives mangy emotions from things’ (qtd. Ades, 1994: 139). Dalí was especially outraged by Jiménez’s famous story Platero y Yo (1914), an account of the poet’s beloved companion Platero, a donkey, and their bland sojourns through pastoral scenes. As Dawn Ades has speculated, Dalí’s violent dislike of this gentle, sentimental story may have contributed to the appearance of the rotting donkey as a visual image in such paintings as Honey Is Sweeter than Blood and as a verbal parody in written communication between Dalí and Lorca. In one such letter dated early December 1927, Dalí signs himself… ‘your ROTTING DONKEY’ and adds, ‘may…Platero…die’ (qtd. Ades, 1994: 139).

Salvador Dalí, Study for Honey is Sweeter than Blood, 1926, oil on wood panel, 37.8 x 46.2 cm, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figures

Dalí’s apparently ferocious distaste for sentimental stories involving human friendships with docile animals did not, it seems, inhibit his affection for the work of the American animator and capitalist entrepreneur Walt Disney. The American film critic James Agee wrote in 1941, that: ‘Disney’s famous cuteness, however richly it may mirror national infantilism, is hard on my stomach’ (qtd. Schickel, 1997: 272). Yet Dalí who had balked at Jiménez’s ‘mangy emotions’ was apparently more tolerant. Indeed he praised the so-called ‘Silly Symphonies’ in an essay published in 1937 in Harper’s Bazaar, and after completing set designs for Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound, took up residence at the Disney headquarters in Burbank California where he produced abundant conceptual paintings for a film that was never completed, the animated short Destino.

Historians of twentieth-century art have largely downplayed the significance of this brief, abortive collaboration, and for good reason. When Dalí undertook the project he was already out of favour with André Breton, the self-appointed magus of Surrealism. Breton was no special admirer of the commercial industries and had earlier warned against those ‘modern poets and artists’ who allowed themselves to pass for ‘mere entertainers,’ and ‘whom the bourgeoisie will never let up on’ (Breton, 2010: 215). Though Breton’s commitment to Marxist ideas was never systematically reflected in his aesthetic ambitions for the movement (leading to various spats with the communist party and with orthodox Marxists both outside and inside the Surrealist group), Surrealism remains broadly defined by its commitment to revolution and the socially-transformative powers of the unconscious—the second gives rise to the first in Breton’s view (see Nadeau, 1978: 208-15).

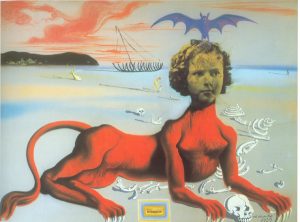

Salvador Dalí, Shirley Temple, the Youngest, Most Sacred Monster of the Cinema in her Time, 1939, wash, pastel, collage on cardboard, 75 x 100 cm, Museum Boijmans Van Beunigen, Rotterdam

The merest suggestion of a ‘Surrealist’ influence on Disney jars in the light of these considerations—but my intention here is not to labour the point of Disney’s ineluctable conservatism. Rather, my main concern is the issue raised in my opening paragraph: that of a rhetorical strategy that aligns sentimental feeling in art with negative un-pleasure. In his abusive satire of Jiménez, Dalí appropriates the sanguine image of the donkey only to corrupt the image (by invoking its death and decay, and by association the ‘abolition’ and ‘destruction’ of Jiménez’s mawkish idealism) (Ades, 1994: 139). But another sense emerges from the conflation of sentimental imagery and bodily putrefaction. This inverted form of the sublime does not rely on the stimulation of anxiety producing delight, as in Edmund Burke’s eighteenth-century definition, but an over-abundance of pleasure leading to psychological pain. Might we draw comparison with Dalí’s 1939 collage of Shirley Temple, in which the juvenile performer’s head appears atop a vicious leonine body surrounded by skeletons? The work is subtitled The Youngest, Most Sacred Monster of the Cinema in her Time. As with the ‘rotting donkey’ motif we might interpret the sphinx as a morbid travesty of sentimental feeling—Shirley Temple was, after all, known for the hysterical excess of her cute persona. But what was Dalí implying when he endowed her with such rapacious cannibalistic tendencies? Are we witness here to the aggressive dimension of kitsch itself, a pun on the violence with which the so called ‘gentle emotions’—the’ “soft” sentiments of kindness and sympathy and the calm passions of delight’ – are so often expressed in kitsch (Solomon, 1991: 2)? We might refer to this violent inflection of kitsch as the sublime of kitsch, the sublime of the sentimental.

In JF Lyotard’s re-reading of Kant, the 20th-century ‘Avant-gardism is[…] present in germ in the Kantian aesthetic of the sublime’ (Lyotard, 1993: 250). In Kant’s definition the sublime is ‘a pleasure mixed with pain,’ that emanates in the ‘cleavage within the subject between what can be conceived and what can be imagined or presented’ – for example an absolutely large or powerful object or event in nature (Lyotard, 1993: 250). For Lyotard this extreme tension or agitation which ‘characterises the pathos of the sublime, as opposed to the calm feeling of beauty’ and which rises from the attempt to figure that which cannot be figured, directly anticipates the modernist pursuit of abstraction as the greatest source of conceptual and spiritual power in aesthetics (Lyotard, 1993: 250). In that sense, according to Lyotard, the twentieth-century avant-garde is a continuation of the eighteenth-century sublime, albeit in a radically different form. The anxiety of the avant-garde resides for Lyotard in the perpetual fear of its own imminent exhaustion or redundancy. This he explains in terms of Edmund Burke’s ‘inquiry’: the barbed pleasure invoked by the sublime is linked specifically to terror – of ‘pain and impending death’(Lyotard, 1993: 251).

It would seem eccentric in the extreme to apply either sense of the term to Disney’s animated work. Surely the Disney brand is recognised for the extent to which it negates the sublime in both its Lyotardian (modernist) and Burkian (gothic) variations. In Disney’s ornamental-realist house-style, we find the sublime ambition to ‘express the inexpressible’ being replaced with a crudely literal form of representation. This visual style is not only relentlessly prosaic (quasi realist as opposed to abstract), it seems deliberately contrived to circumvent any potential mystery or ambivalence arising in the plasticity of the form. As Richard Schickel complained in his book The Disney Version (published in 1968); the depiction of animal life in the films all-too-often erred towards ‘conventionalised, commercialised images of cuteness – fluffy, cuddly and saucy’(Schickel, 1997: 176). These objects have of course the further effect of diminishing the ‘terror of pain and death,’ inherent in the Burkian sublime. Schickel cites the famous episode in Snow White (1937), when the animals and the dwarfs rush to save the heroine from being poisoned by the Witch, and the ‘gambolling presence’ of the creatures ‘serves to reassure, even to provide a few small laughs’ along the way (Schickel, 1997: 177).

Snow White, 1937, dir. David Hand, Disney (film still)

What Schickel does not acknowledge is that the scene in question is full of the archetypal material of the eighteenth-century sublime – awesome and malignant images of nature (forests, mountains, darkness, storms) – not to mention the underlying theme of infanticide, of grand guignol violent intrigue and murder (which remains intact in spite of Disney’s anxious bowdlerisation of the Grimm tale). In other words, Disney’s predilection for the cute, for a relentless return to optimism, serves to violate the sublime potential inherent in his own subject-matter. As such the viewer experiences the negation of the sublime as a kind of rhetorical gesture or action, whereby the promise of the sublime is itself violently withdrawn. This sensation of loss – received from the apparent absence of the sublime – depends on the viewer’s internalisation of what we might call the rules or conventions of the sublime. That is, the sublime must, to some extent, be anticipated in order for it to be missed when it does not arise. This is most obviously a postmodernist phenomenon and might be seen as confined to those initiates, the privileged minority familiar enough with the historical and contemporary avant-gardes to accept their provocations as standards. But Schickel’s notorious repudiation of Disney (published in the late 1960s) was itself symptomatic of the assimilation of avant-garde aesthetics into elite-bourgeois culture. Disney’s hyper-decorative, pseudo-gothic animation-style appeared, even to the middle-brow, lamentably reactionary: ‘an art of limited – some would say – none-existent sensibility…that refused to consider the possibilities inherent in the dictum that less is more’ (Schickel, 1997: 178). Schickel’s agenda, in denouncing what he saw as Disney’s ‘trifling realism’ was not, then, radically Marxist, but soundly of the establishment, reflecting the widespread contemporary assumption that pared-down modernism was the most advanced and (and for the properly acculturated spectator) affirmative aesthetic form.

It is well known that Disney hated for his films to be confused with high-culture, that the aesthetics of the avant-garde were threatening to his wholesome populist values and commercial ambitions in Hollywood. His sentimental forms can thus be seen as aggressively disposed towards a potentially corrupting modernism. This defensive counter-aesthetic becomes sublime when manifested with a rhetorical aggression analogous to the archetypal incendiary violence – the will to shock – of the avant-garde itself. ‘”The Sublime,’ writes Lyotard, quoting the eighteenth-century poet, Boileau, ‘is…a marvel, which seizes one, strikes one, and makes one feel.” The very imperfections, the distortions of taste, even ugliness, have their share in the shock-effect’ (Lyotard, 1993: 249). For sentimental art to be sublime it must likewise ‘strike’ and ‘seize’, and it must tend towards distortion, imperfection and ugliness. Consider how the ‘cute’ aesthetic grotesquely contorts the physiognomy of its objects—as Daniel Harris puts it: the ‘gout-stricken ankles’ of one unfortunate doll ‘crammed into booties’; the ‘astonishingly candid eyes’ of another, two ‘moist pools’ devoid of ‘internal life’ and ‘composing at least 25 percent of a face as wide as her shoulders.’ (Harris, 2000: 3, 1-2). Consider further the scenes in Snow White in which small creatures assist the heroine in the accomplishment of domestic tasks, their claws rolling up cobwebs and embellishing the crusts of pies. In ‘The Human Face’ Georges Bataille wrote in horror of ‘wasp-waisted corsets scattered throughout provincial attics,’ that are ‘the prey of moths and flies, the hunting grounds of spiders’ (Bataille, 1986: 21). In Cinderella (1950), it is not spiders but mice that swarm upon the discarded female vestments—still this image would be rather horrible if not for the whimsical impression of thrifty Lilliputian construction-workers.

Snow White, 1937, dir. David Hand, Disney (film still)

Many commentators, following on from Clement Greenberg (in his 1939 essay ‘Avant-Garde and Kitsch’), came to regard mass-culture as a pollutant, a kind of disease or infection that threatens the efficacy and purity of the avant-garde. In Formless: A User’s Guide, Yve Alain-Bois refers to the ‘scatological’ implications of kitsch: a concept derived in turn from Theodore Adorno’s view of kitsch as a ‘poisonous’ substance mixed in with art (Bois, 1999: 120). As Adorno himself puts it (in his Aesthetic Theory):

Kitsch is not, as those believers in erudite culture would like to imagine, the mere refuse of art, originating in disloyal accommodation to the enemy; rather, it lurks in art, awaiting ever recurring opportunities to spring forth… (Adorno, 1999: 239).

What the Disney aesthetic embodies is not kitsch as poison lurking within art, but the sublime as poison lurking within Disney’s peculiar forms of kitsch, ‘awaiting ever recurring opportunities to spring forth’. It is highly appropriate that, when the Queen incants over her poisoned apple, the fluids rolling on its surface assume, momentarily, the drifting shape of a skull, before the phantom-sign fades and the object glows red and pure. Such an image encapsulates perfectly the idea of a noxious sweetness—like the pejorative view of sentimental art itself—a kitsch that kills, a variation on the ‘terrifying and edible beauty’ to which Dalí himself was enthralled (Dalí, 1998: 198).

This paper was written for Everydayness and the Event, the Centre for Modernist Studies annual conference 2013, and delivered by proxy at the University of Sussex Brighton, on 30th August 2013.

REFERENCES

Ades, Dawn. ‘Morphologies of Desire’. in Salvador Dalí: The Early Years. ed. Michael Raeburn. (London: The South Bank Centre, 1994).

Adorno, Theodor W. Aesthetic Theory. Gretel Adorno and Rolf Tiedemann ed. Robert Hullot-Kentor trans. 2nd ed. (London: The Althone Press, 1999).

Bataille, Georges. ‘Human Face.’ ‘Figure humaine.’ Documents, no.4, 1929. trans. Annette Michelson. reprinted in October. Vol. 36. Georges Bataile: Writings on Laughter, Sacrifice, Nietzsche, Un-Knowing (Spring, 1986).

Bois, Yve-Alain. ‘Kitsch’. in Formless: A Users Guide. 2nd ed. Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind E. Krauss, (Cambridge, Mass.; London: MIT Press, 1999).

Breton, André. Manifestoes of Surrealism. trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane. 5th ed. (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2010).

Dalí, Salvador. The Collected Writings of Salvador Dalí. ed. and trans. Haim Finklestein. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

__________. ‘Surrealism in Hollywood’. in Dalí and Film. ed. Matthew Gale. (London: Tate, 2007). pp. 154-156.

Harris, Daniel. Cute, Quaint, Hungry and Romantic: The Aesthetics of Consumerism. (New York: Basic Books: 2000).

Lyotard, J.F. ‘The Sublime and the Avant-gard’. in Postmodernism: A Reader. Thomas Docherty ed. (London: Longman, 1993).

Nadeau, Maurice. The History of Surrealism. trans. Richard Howard. (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978).

Schickel, Richard. The Disney Version: The Life, Art and Commerce of Walt Disney 3d. ed, (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1997).

Solomon, Robert C. ‘On Kitsch and Sentimentality’. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 49, (Winter, 1991).